Did you know that the U.S. Constitution starts with the word "but" not once but seven times?

"But in all such Cases the Votes of both Houses shall be determined by yeas and Nays, and the Names of the Persons voting for and against the Bill shall be entered on the Journal of each House respectively." - US Constitution

Thus, unlike what most people are taught in elementary school, "but" can be used in front of a sentence, and this placement is grammatically correct.

"Contrary to what your high school English teacher told you, there’s no reason not to begin a sentence with but or and; in fact, these words often make a sentence more forceful and graceful. They are almost always better than beginning with however or additionally." - Kingsley Amis, The King's English

So why are we told in school not to use "but" in the beginning of a sentence? The short answer is because of an age-old English classroom rule.

Table of content

- What does "but" mean?

- How to pronounce "but"

- The origin of the "English classroom rule"

- Is it grammatically correct to start a sentence with "but"?

- How should we start a sentence with the word "but"

- Is it formal to start a sentence with "but"?

- But vs. however

- Alternative phrases

- Other age-old grammar rules of which we can do without

What does "but" mean?

"But" is one of seven coordinating conjunctions.

What are coordinating conjunctions?

Coordinating conjunctions are words that link words, phrases or clauses that are similar in importance within a sentence.

1. And: Connects two elements that are similar or of equal importance.

- Example: I like tea and coffee.

2. But: Indicates a contrast or exception between two elements.

- Example: She is smart, but she is also humble.

3. Or: Presents an alternative or choice between two elements.

- Example: You can have pizza or pasta for dinner.

4. Nor: Used to indicate a negative alternative.

- Example: She neither likes tea nor coffee.

5. For: Explains the reason or purpose.

- Example: He studied hard, for he wanted to pass the exam.

6. Yet: Indicates contrast or concession.

- Example: She worked hard, yet she couldn't finish on time.

7. So: Indicates a result or consequence.

- Example: It was raining, so we stayed indoors.

But

Parts of speech: conjunction

1. Contrast: Used to connect two clauses that have opposing ideas.

- Example: The cake looked delicious, but it tasted burnt.

2. Exception: Introduces an exception to a general statement.

- Example: I like all vegetables, but I don't like broccoli.

3. Contrast within a Sentence: Creates a contrast within one sentence.

- Example: He wasn't sure if he should go, but curiosity got the better of him.

4. Emphasis (informal): used for emphasis, often placed before the word or phrase being emphasized.

- Example: I told you not to touch it, but did you listen?

How to pronounce "but"

In American and British English, "but" is one syllable and is pronounced as it is spelled: "but."

The origin of the "English classroom rule"

In "The Story of English in 100 Words" by the linguist David Crystal, the author mentions that this rule first originated in the nineteenth century when students began repeatedly using "but" to start their sentences.

To counteract this problem in the 18th century, teachers shifted their emphasis from teaching the proper usage of coordinating conjunctions to instructing students not to start a sentence with "but." Although their method was understandable and possibly needed at the time, it would have been better if this guideline had been taught later in the students' educational journey as a guideline rather than a grammar rule.

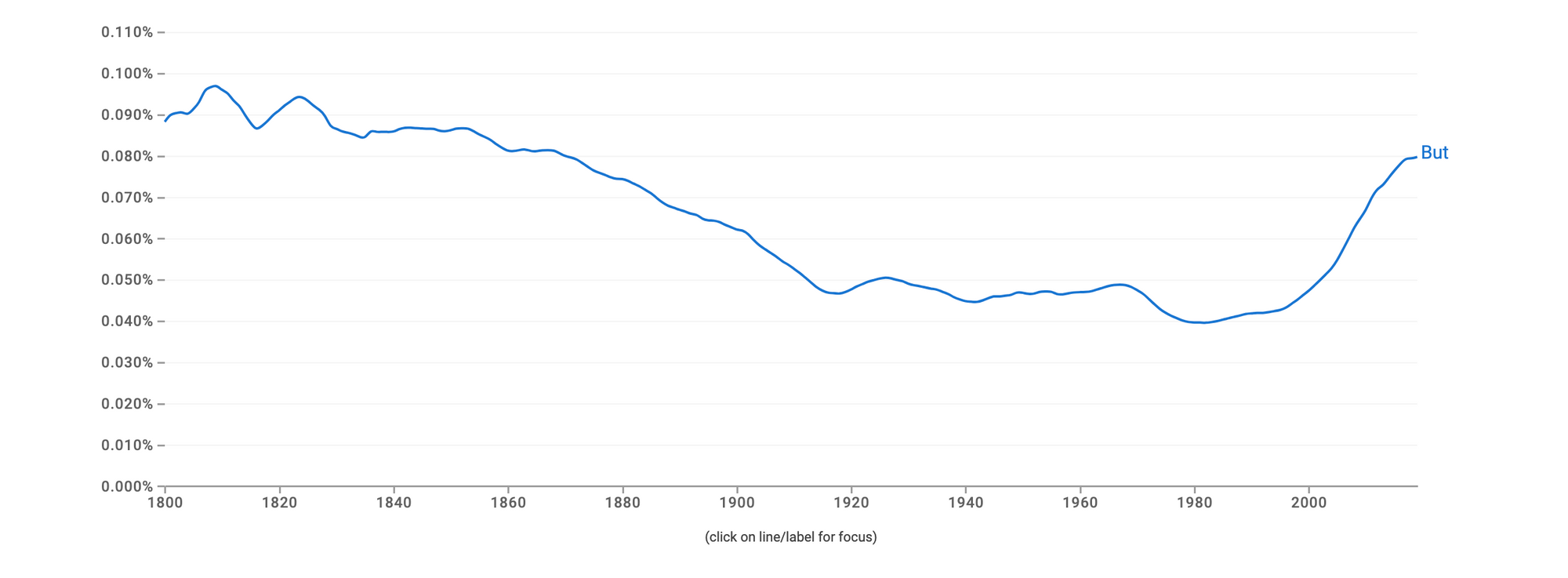

The Ngram graph, which records words from all written works on the internet, also attests to this fact, as the word "But" (with a capital B) occurred most frequently in the beginning of the 1800s and declined over time.

An example sentence with too many "buts":

But she wanted to visit the zoo. But it was raining. But she packed her umbrella. But she forgot her raincoat. But she didn't mind getting wet. But then she remembered she had plans later. But she decided to go anyway. But when she arrived, she found out the zoo was closed. But she laughed it off and went for ice cream instead.

In the example above, we can see that starting many sentences with "but" can be disorienting and unnecessary. While relying on "but" to join and compare sentences is acceptable, excessive use can obscure the sentence's meaning and readability. Furthermore, it hinders the learning process, as students do not explore alternative ways to join sentences fluidly.

We have revised the paragraph using alternative words/phrases:

She wanted to visit the zoo, but it was raining. Despite the rain, she packed her umbrella. However, she forgot her raincoat. Nevertheless, she didn't mind getting wet. Later, she remembered she had plans. Nonetheless, she decided to go to the zoo anyway. Upon arrival, she discovered it was closed. Instead, she laughed it off and went for ice cream.

Which one sounds better to you?

It would definitely be the second paragraph.

Is it grammatically correct to start a sentence with "but"?

The short answer is yes, it is.

The focus should not be on the location of "but" in a sentence, but rather on the emphasis, formality, and style of the sentence. The real question should be, "What purpose should the word "but" serve at the beginning of a sentence?" If it is for comparative use, then yes, we should incorporate it at the beginning.

How should we start a sentence with the word "but"

Yes, we can place "but" at the beginning of a sentence, but the writer should be intentional in its usage.

"But" should be used for comparison. Great writers have often used "but" at the beginning of sentences. The New York Times frequently features front pages with news articles filled with sentences that start with "but."

Examples from great writers:

Hans Christian Andersen, "The Emperor's New Clothes":

'But the Emperor has nothing on at all!' cried a little child.

Matthew Arnold, "Culture and Anarchy (1869)":

But that vast portion, lastly, of the working-class which, raw and half-developed, has long lain half-hidden amidst its poverty and squalor, and is now issuing from its hiding-place to assert an Englishman's heaven-born privilege of doing as he likes, and is beginning to perplex us by marching where it likes, meeting where it likes, bawling what it likes, breaking what it likes—to this vast residuum we may with great propriety give the name of Populace.

Walter Bagehot, "The English Constitution (1867)":

But of all the nations in the world the English are perhaps the least a nation of pure philosophers.

Isaiah Berlin, "Four Essays on on Liberty":

Injustice, poverty, slavery, ignorance—these may be cured by reform or revolution. But men do not live only by fighting evils.

"The Bible (King James version)":

But of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, thou shalt not eat of it: for in the day that thou eatest thereof thou shalt surely die.

Is it formal to start a sentence with "but"?

Many people advise against starting a sentence with "but" in formal settings, but this is not true. Many stylistic and English specialists even argue that "but" could be the best word to use in formal situations, as it is the most effective word for comparing two words, phrases, or sentences.

"Perhaps we can all agree that beginning a sentence with but isn’t wrong, slipshod, loose, or the like. But is it less formal? I don’t think so. In fact, the question doesn’t even reside on the plane of formality. The question I’d pose is, What is the best word to do the job?" - Bryan A. Garner

Legal

Although many lawyers avoid using "but" at the start of a sentence, this placement is correct. Bryan A. Garner, the author of many renowned books on legal writing, has agreed with this guideline many times in his various books.

There is some debate among lawyers regarding its usage, but many agree that using "but" at the start of a sentence is clearer, more concise, and beneficial for persuasive writing.

Examples:

From a judicial opinion in 2013. City of Arlington v. FCC, 569 U.S. 290, 305 (2013):

“But this case has nothing to do with federalism.”

From a judicial opinion in 1901, Colburn v. Grant, 181 U.S. 601, 607:

“But this is not sufficient.”

From a judicial opinion in 1793, Chisholm v. Georgia, 2 U.S. 419, 422:

“But this redress goes only half way.”

From an appellate brief in 2003, Alaska Dept. of Envtl. Conservation v. EPA, 2003 WL 2010655 at 46 (U.S. Pet. Brief 2003):

“But the EPA cannot claim that ADEC’s decision was unreasoned.”

Academic

As it is grammatically correct to start a sentence with "but," there is nothing wrong with doing so in academia. However, professors or teachers might have different ideas about this guideline, so the best advice would be to conform to their standards.

Examples:

"United States Health Care Reform Progress to Date and Next Steps" - Barack Obama

"But we also need to reinforce the sense of mission in health care that brought us an affordable polio vaccine and widely available penicillin."

Business

Business writing has changed over the past century. No longer is it the stuffy, authoritarian, and corporate-style writing. Business writing should be authoritative, trustworthy, and well-written, but the emphasis is not on sounding important; it's about getting the message across.

Following the old conventions of avoiding "but" to start a sentence should be something that is part of this transition. As this rule was not based on proper grammar rules but on teaching adjustments at the time, it is fine to begin with "but."

Examples:

Satya Nadella (CEO of Microsoft) first email to the employees at Microsoft:

"Many companies aspire to change the world. But very few have all the elements required: talent, resources, and perseverance. Microsoft has proven that it has all three in abundance. And as the new CEO, I can’t ask for a better foundation."

But vs. however

Many people opt to use "however" in formal situations instead of "but." For academic writing, we would not use "however" in place of "but." However, it is important to understand that the more important factor would be the purpose of the conjunction in the sentence.

Let's talk briefly about "however."

However" is a conjunctive adverb. Conjunctive adverbs can't join two independent clauses by themselves with just a comma. They typically need a semicolon or a comma with a conjunction like "and" or "but" for proper punctuation.

For instance, in the conjunction use, it indicates a contrast or introduces a point that qualifies the previous statement.

An example would be, "The movie was quite long; however, it was very well acted."

In its adverb use, "however" emphasizes that something remains true despite the previous statement. For example, "I'm all out of milk; however, we still have some cheese."

Now, let's change a sentence that uses "but" to"however."

But: But I still believe we can find a solution to this problem.

However: I still believe, however, that we can find a solution to this problem.

Alternative phrases

- Nonetheless

- On the other hand

- In contrast

- Conversely

- Nevertheless

- Yet

- Whereas

- Although

- Despite this

- In spite of that

Other age-old grammar rules of which we can do without.

The following are other grammar rules that Steven Pinker believes are no longer relevant in the changing landscape of language.

Steven Pinker is a Harvard psycholinguist who has written several books on developmental linguistics. He wrote this article, "10 'Grammar Rules' It's OK To Break (Sometimes)," which was published in The Guardian.

Bear in mind that Steven Pinker is a descriptivist. What is a descriptivist, you ask? Descriptivists observe and analyze how language is actually used by speakers in a particular community or culture, rather than prescribing how it "should" be used based on rules or standards set by authorities.

We have scrutinized the other nine rules and added a brief opinion on each of Pinker's rules. The opinion was formulated from various grammar guides and internet research.

Split infinitives

A lot of debate has surrounded split infinitives, but post-1960s grammarians seem to agree that split infinitives are correct and should be used to emphasize certain parts of the sentence.

- Clarity: Sometimes, placing an adverb between "to" and the verb makes the sentence much clearer. For instance, she decided to carefully examine the evidence. Here, "carefully" modifies "examine," not "decided," and splitting the infinitive clarifies that.

- Flow and emphasis: Splitting an infinitive can create a more natural rhythm or emphasize a particular word. Consider: "The stars seemed to twinkle brightly in the night sky." Splitting the infinitive with "brightly" puts the emphasis on how the stars twinkled.

Opinion: We agree with Pinker's thoughts here. Split infinitives are fine to use and should be encouraged if they help make the sentence more clear and fluid.

Very unique

This word plays on the difference between grammar and logic. Grammar and logic do not always align. From a logical and semantic standpoint, "very unique" is considered incorrect because "unique" itself implies being the only one of its kind. Something cannot be "very unique" because uniqueness does not have degrees. It is either unique or not. From a syntax (grammar) standpoint, the combination of "very" with "unique" is technically correct.

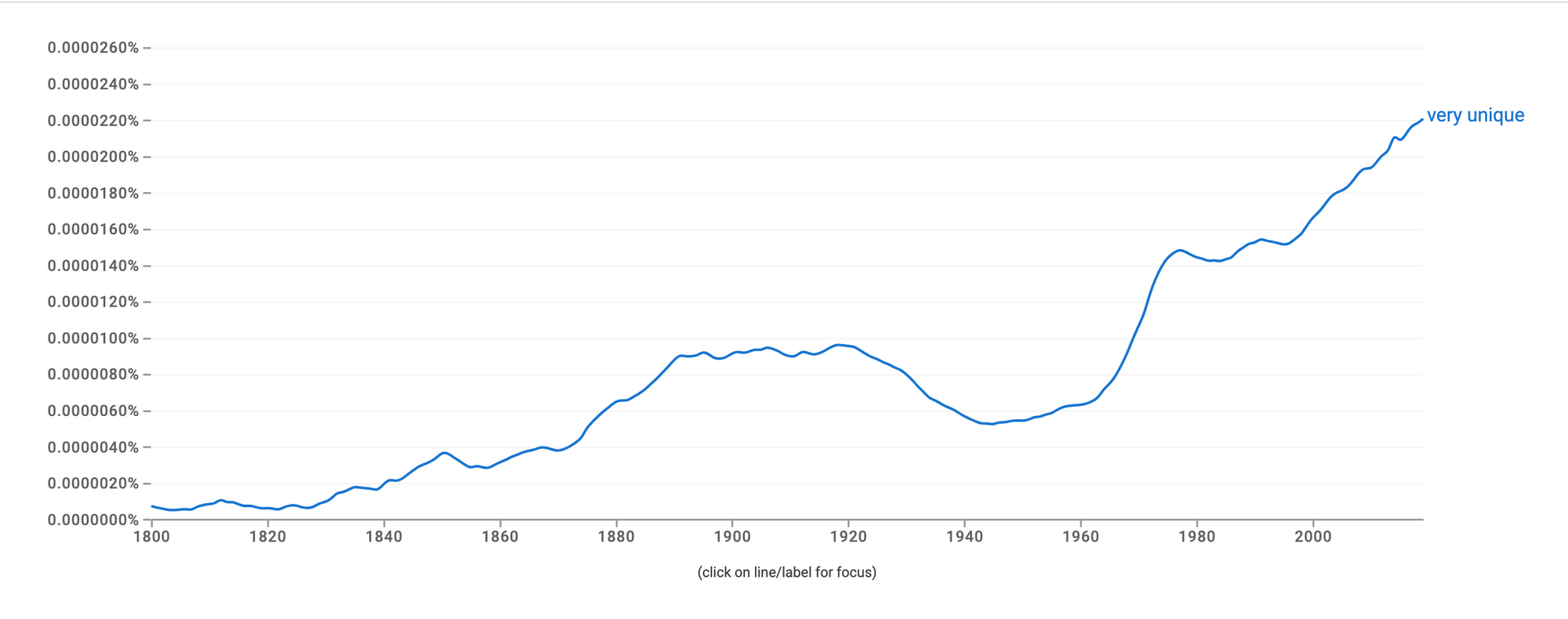

Due to the frequency of the occurrence of "very unique," the term has become more acceptable in everyday discourse. If you examine the Ngram graph below, you can see that "very unique" has been increasing in usage over time.

Opinion: We agree with Pinker on this one. Since it is not grammatically incorrect and "very unique" has been used quite regularly in recent years, we see no problem with using "very unique" in sentences.

Of course, we should be mindful of how we use "very unique." If it is used for every instance of uniqueness, readers of your written work may become more skeptical of both the use of "very unique" and "unique."

That vs. which

The debate between "that" vs. "which" is interesting because these two terms differ depending on the region. There's a bit more flexibility in using "that" and "which" in British English compared to American English.

Standard usage (applies to both British and American English):

That: Introduces restrictive clauses. These clauses define a specific element within a larger group and are essential to the meaning of the sentence. They don't have commas around them.

- Example: The book that I borrowed is on the table. (This specifies which book you're talking about.)

Which: Introduces nonrestrictive clauses. These clauses provide additional, non-essential information about something already identified. They are not defining and can be removed without changing the core meaning. They are usually set apart by commas or dashes (which adds a pause when spoken).

- Example: The house, which my grandparents built, is mine. (This adds a detail about the house but doesn't define which house is yours.)

British English flexibility:

"Which" for restrictive clauses: In British English, it's sometimes acceptable to use "which" even in restrictive clauses, where American English would use "that." This can be seen more in informal contexts or older writing styles.

- Example (British English, Restrictive): The house which has the red door is mine. (While grammatically correct in British English, "that" would be more common in American English.)

But there’s simply no good reason, he says, why we can’t use “which” freely, as the Brits already do, to refer to things both essential and non-. “Great writers have been using it for centuries" - Pinker

Rule: Pinker believes that there is no reason for Americans not to apply "which" to restrictive clauses as well. We believe that this rule depends on the sentence. The importance should be on whether the sentence reads well, not on whether we are applying the restrictive and nonrestrictive clause correctly.

Who vs. Whom

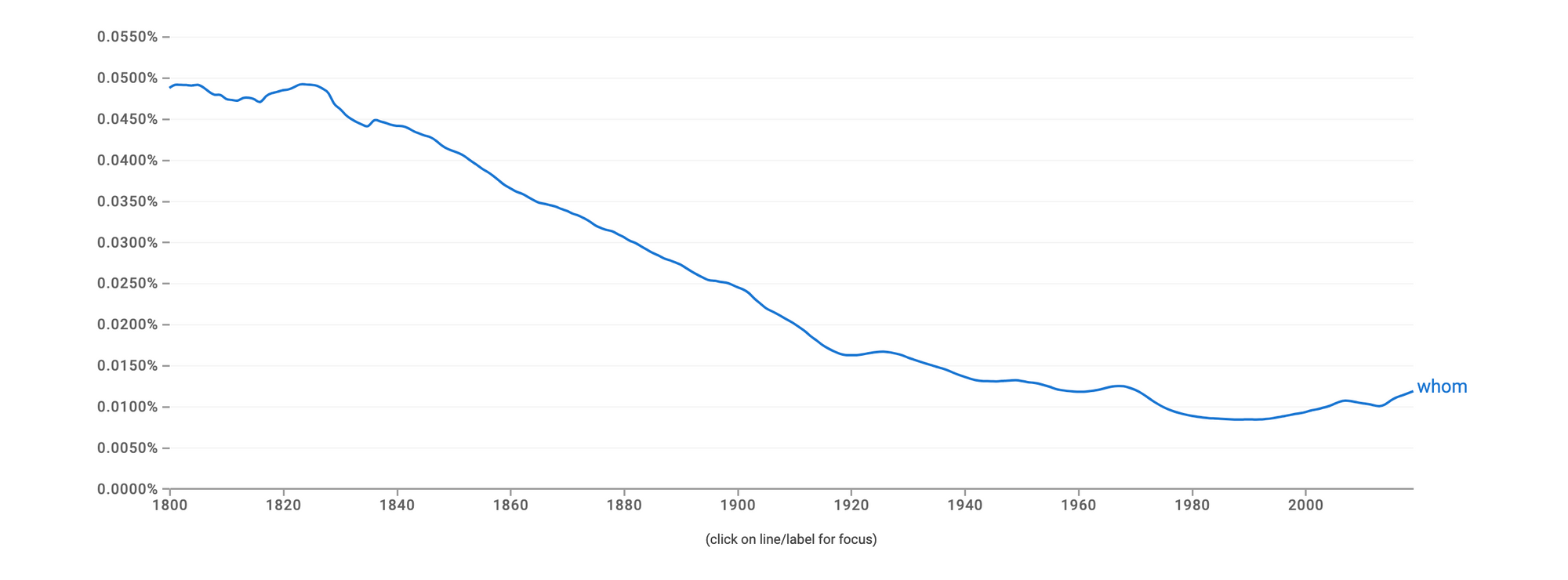

Pinker states that we should do away with the antiquated "whom," which most people do not know how to use properly, causing many people to avoid its usage. This Ngram graph attests to the fact that "whom" has decreased in use since the 1800s.

Here's the difference between who and whom:

- Who: Use "who" when referring to the subject of a verb or clause.

- Whom: Use "whom" when referring to the object of a verb or preposition.

Simple trick:

- Try replacing "who" or "whom" with "he/she" or "him/her." If "he/she" sounds natural, use "who." If "him/her" sounds natural, use "whom."

Rule: Although it's true that "whom" has decreased in use, it is still a relevant grammar rule that is taught in schools and should be applied in your written work. Thus, we must adhere to the confines of traditional grammar rules for this one.

Fused participles

Some grammarians believe that gerunds should always take the possessive form, but Pinker believes this grammar rule can be broken. This supposed error of not placing a possessive form before a gerund was given a name, "fused participle," by H.W. Fowler in his book "A Dictionary of Modern English Usage."

Fused Participle:

- Problem: A fused participle occurs when a gerund (verb ending in "-ing" used as a noun) follows a noun or pronoun without the possessive form, creating ambiguity about who or what performs the action.

- Example: Walking down the street, a mailbox appeared. (Who was walking?)

Here are some examples when fused participle was okay:

- The company's downsizing has affected morale. (This clarifies whose downsizing is being referred to.)

- Non-possessive is okay (informal): Downsizing can have a negative impact on employees. (Here, the context implies a general "downsizing" and the sentence is clear.)

Rule: We are with Pinker on this, and we believe that gerunds do not need to be preceded by a possessive. Not every situation requires a possessive gerund. If the sentence is clear without it, you can use the non-possessive form.

That said, in formal writing, using possessive gerunds is more common to ensure clarity and proper grammar. Informal writing allows for more flexibility.

"Like" vs. "as"

In 1954, R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company used the slogan, "Winston tastes good, like a cigarette should." Purists and other tobacco companies criticized the company's use of "like," saying that it can only be used with a noun phrase because it is a preposition. For example, "he was fast like a cheetah."

But is this true? Pinker believes "like" and "as" are the same, with "as" being the more formal version of the two. He also states that "like" and "such as" can both be used to show examples, in contrast to what many people believe.

Rule: We are with Pinker on this one.

Possessive antecedents must precede possessive adjectives

Pinker believed that the above rule was not always true if the antecedent is clear. However, some people believe that the possessive antecedents must directly precede the possessive adjective.

Examples of a possessive antecedent preceding directly before a possessive adjectives:

- My phone is ringing. (It's clear whose phone is ringing - "my" refers to the speaker.)

- The children played with their toys in the sandbox. (We know the toys belong to the children because "their" follows "children.")

- We visited Paris's famous landmarks. ("Paris" is the city that owns the landmarks.)

Pinker's version of a grammatically correct sentence:

For example, This restaurant is known for its (restaurant's) delicious seafood. ("Restaurant" is close enough to "its" for clarity.)

Pinker's version of a grammatically incorrect sentence:

- I saw his hat on the table. (Whose hat? The sentence is unclear without mentioning the owner first.)

Rule: We stand by Pinker's opinion.

A sentence should not end on a preposition

“The spurious rule about not ending sentences with prepositions is a remnant of Latin grammar, in which a preposition was the one word that a writer could not end a sentence with.” - Bryan Garner

The misconception that sentences should not end with a preposition comes from Latin influences. In the 18th and 19th centuries, some purists believed that English should follow Latin grammar and discouraged the use of prepositions at the end of sentences because of their sentence structure. Pinker believed this rule was no longer relevant.

However, nowhere does it say that putting a preposition at the end of a sentence is wrong. This placement can help the sentence have a natural flow, emphasis, or clarity.

Rule: Although we believe that you can end sentences with a preposition, if you want to exercise caution, you should revise your sentences so that prepositions do not trail at the end.

A pronoun serving as the complement of "be" must be in the nominative case (I, he, she, we, they)

This rule is influenced by the views of 18th and 19th-century grammarians who believed in strict adherence to Latin grammar rules. However, Pinker provides an example of inconsistency with this grammar rule.

An example of this inconsistency is that a statement like "'hi, it's me,'" would be considered incorrect according to this rule, but everyone uses this phrase in casual language.

This statement refers to the grammatical rule that when a pronoun functions as the complement of the verb "be" (such as "is," "am," "are," "was," "were," etc.), it should be in the nominative case.

Examples:

- Correct: "It is I." ("I" is in the nominative case.)

- Incorrect: "It is me." (Although commonly used in informal speech, "me" is technically incorrect here according to traditional grammar rules.)

- Correct: "He is she." ("She" is in the nominative case.)

- Incorrect: "He is her." ("Her" is incorrect here; it should be "she.")

Rule: Although Pinker is correct in stating that "hi, it's me" is used in everyday speech, we should use the appropriate one depending on the situation.

In formal writing or when adhering strictly to traditional grammar rules, using the nominative case after "be" is considered more correct. However, it's worth noting that in casual or colloquial speech, the objective case can be used ("it's me," "it's her," etc.).

"Than" and "as" need to precede clauses, not noun phrases

According to many stylistic grammar guides, "rose is smarter than him" is considered incorrect, while "rose is smarter than he" is considered correct, with the latter being the formal choice, as per Pinker's view.

Correct usage with clauses:

- "She runs faster than he does." (The clause "he does" follows "than.")

- "He is as tall as she is." (The clause "she is" follows "as.")

Example usage with noun phrases:

- "She runs faster than him." (This is technically incorrect because "than" should be followed by a clause. However, it's commonly used in informal speech.)

Rule: Pinker was correct to some extent on this matter, but we should also make a clear distinction between when to use each variation. For informal cases, you can use noun phrases, but for more formal situations, be mindful to use a clause.

New words and usages degrade the language

Language is constantly evolving, and Pinker believed that "language is living" and that we shouldn't constrict our vocabulary to that of a dictionary. Pinker was part of the descriptivist movement. The descriptivist movement is an approach to linguistics and language study that focuses on describing and analyzing how language is actually used by speakers, rather than prescribing how it should be used according to traditional rules or norms.

Rule: You should stick to the dictionary for this one, as new words are wonderful, but they take time to be accepted as words, so we should stick to the traditional conventions of diction.

Conclusion

In a New Yorker article, Nathan Teller summarizes our viewpoints of Pinker's 10 rules perfectly:

"At such times, it is difficult to shake the suspicion that Pinker’s list of “screwball” rules simply seeks to justify bad habits that certain people would rather not be bothered to unlearn."

Some of these rules have validity, but we should be careful not to push the boundaries of grammar rules if we don't have full mastery of English. We should practice precision with the traditional rules.

10 Old-School Grammar Rules That Teachers Need To Ditch Steven Pinker: 10 'grammar rules' it's OK to break (sometimes) Beginning a sentence with “however” in legal writing? Steven Pinker’s Bad Grammar Descriptivism vs Prescriptivism 10 popular grammar myths debunked by a Harvard linguist On Beginning Sentences with a But Satya Nadella email to employees on first day as CEO 10 new rules of business writing Beginning with “but”